Sympathy for Satan: Milton's Paradise Lost

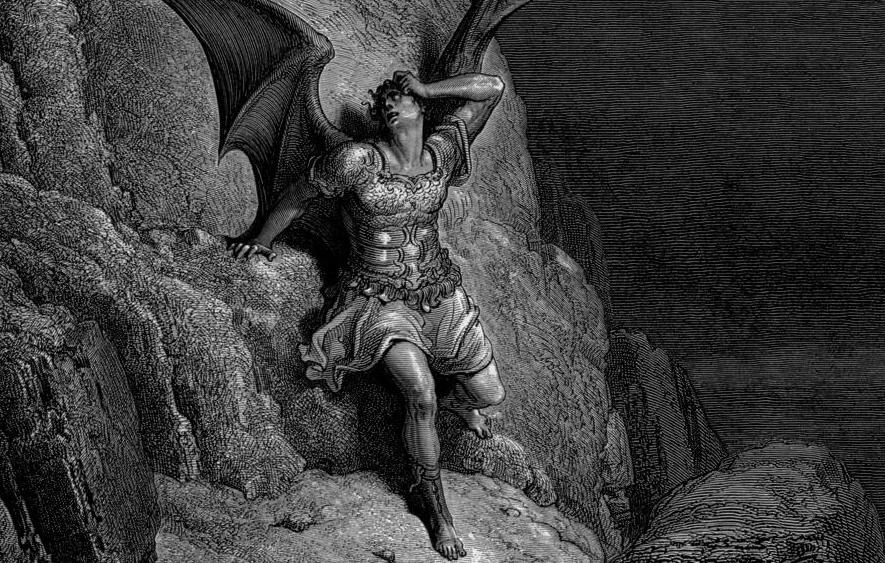

Gustave Doré (1866)

For the purposes of this essay it is important to clarify that I am approaching Milton’s epic, Paradise Lost, with a literary lens, not a religious lens. Many have argued over Milton’s character of Satan and I find that a major cause for this conflict lies in the conflation of the religious Satan and Milton’s literary character in Paradise Lost; one is seen as literal, the other as figurative. When Milton writes of Satan, he writes not of a sociopathic evil force or irreligious philosophy, but a humanized and damned soul. Throughout my research I have found it more suitable and charitable to Milton to view his Satan as a literary character serving as an allegory for fallen humanity as opposed to a true depiction of a literal, spiritual, soulless being nor an absurd literary villain to Christ. Therefore, for the purpose of this essay I will begin with the literary lens examining the Satan character whom Milton anthropomorphizes and only then move onto the Satan whom Milton viewed as a real and immediate enemy.

There are many types of literary characters: three of which are 1. the Classic Hero, 2. the Tragic Hero, and 3. the Antihero. To help define ‘antihero’ for this essay, it is important to clarify the distinction between antihero and tragic hero. In my definitions, the classic hero (in the general sense) is a protagonist (leading character) overcoming what would have been their hamartia (a cognitive or moral error made by the protagonist in a dramatic plot or “perfect tragedy” [Aristotle 32, 93]) and/or trying to save the world (the Son, Superman, Frodo, Odysseus etc); A tragic hero is a character who succumbs to their hamartia, but eventually overcomes it with a redemptive humility before they die, effectually being "too late”, already suffering the tragic consequences of their error (Adam, King Lear, Oedipus Rex, Samson Agonistes etc); The antihero is a villain-protagonist who is also consumed by their hamartia, experiences the impulse to yield to redemptive humility, but after much inner conflict obstinately rejects it for reasons usually rooted in stubborn pride and/or passion for suffering (Satan, Macbeth, Raskolnikov, etc). In view of this comparative definition of ‘antihero’ and how we see Milton express Satan’s inner conflicts through his soliloquy’s, as well as being the protagonist in the first narrative arc, I am confident in saying that Milton created one of the earliest antiheroes in literature through Satan of Paradise Lost.

Milton’s depiction of Satan as an antihero inspires the reader to become simultaneously sympathetic of and repulsed by Satan’s story. In this essay I will argue that this sympathetic/repulsed reader response may guide readers to better understand their own corruption and how their response to their sin determines their destiny. In my first section I will outline exactly how readers of Paradise Lost become sympathetic towards the antihero while simultaneously repulsed. Here I will also address criticisms against this sympathetic reader response. In the latter part of this essay I will outline how one can gleam inner truth and self-revelation through Satan’s tragically deserved self-damnation.

1. THE SYMPATHETIC ANTIHERO:

Shawcross says that an anti hero “does not accept life as it is [or] things as they are … An antihero is not simply a nonhero or one opposed to the hero; [they] are a specific personality, explainable in psychological terms,” (35, 36). The psychological makeup of an antihero, Shawcross continues, is that of Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov: “Like Satan, [Raskolnikov] reasons in extreme alternatives only: "Either to be a hero or to grovel in the mud—there was nothing between. That was my ruin’,” (36; Dostoevesky 39). Shawcross goes on to remark that as one defiles themself in the mud, one can falsely redeem their story as a martyr; a self-sacrificial hero. This is where the antihero psychology comes into play; suffering becomes a passion, a means to a false redemption. This definition perfectly fits with Satan of Paradise Lost while he admits his own sacrificial duty to his followers in Book 4, line 388. Yes, this psychology can be said to be absurd, and yet still not without sympathetic worth.

An antihero, in my elaboration of Shawcross’s definition, must be a villain whom the reader can see themselves in. It is a character with motives and perceptions which the reader can understand while simultaneously see through and reject. One can acknowledge the virtue of Satan’s motives, but still recognize how these virtues have been corrupted: Satan’s bravery, fight for freedom/against tyranny, self-awareness of limitations, loyalty to followers, etc. The major vice, in which no virtue is found that Satan embodies is still one which all are familiar with. This pure vice is the conscious sin, undisguised and laid bare: The crime of overwhelming passion, anger, and bitterness.

The compelling power of the antihero lies in how he/she causes the reader to root for the redemption of the villain without forsaking the justice which is compassionately due to said villain. Satan says in Book IV, “By conquering this new world compels me now/To do what else, though damned, I should abhor" (4.391-392). This line shows us Satan’s own hatred of who he is and what he is about to do, inspiring sympathy in the reader and hope for his own transformative redemption. He says again in Book IX, “To basest things. Revenge at first though sweet/Bitter ere long back on it self recoils" (9.171-72). Satan understands his own dilemma of bitter suffering with or without revenge on his Creator. The absurdity of his actions is apparent to him yet he feels he has no other choice for he cannot imagine being free of said suffering.

Milton’s most poignant way to inspire sympathy for Satan is in his soliloquy’s, confessing his feeling of being trapped in his destiny to be God’s adversary. Satan serves as a mirror the reader can look into and subsequently find themselves rooting for his deliverance, yelling at the page, “There is still hope and grace! Repent!”. Not only does the reader hope for Satan’s reconciliation with God for the good of Adam and Eve, or even for the good of humanity, but for the good of the salvation of the Devil and his fallen angels. And yet the reason Satan is not a hero, but one whom the reader must repulse, is because of the infernal stubbornness and hopeless hardness of his mind and heart, “not to be changed by place or time …” (1.249-255).

1.1 CRITICISMS

Stanley Fish argues that Milton’s interjections amid Satan’s soliloquy’s are to protect the reader from feeling anything except vigilance and skepticism towards the devil’s heartless words. (Fish 9-13; Milton 1.125-6). As the reader and Milton recognize the duplicity of his motives, any sympathy for Satan accordingly dissipates. Alternatively, Stein approaches this duplicity with a deeper understanding of the mystery of Satan’s pride: “He cannot repent, he says, because of his ‘dread of shame’ before his followers,” (5). As Satan recognizes his own ulterior motive in Book 4, lines 79-84, dreading his own shame and disappointment to his followers if he were to repent, the criticism of Satan’s stubbornness still stands without stripping him of all sympathetic worth; for all are capable of understanding the fear of disappointing those who trust us. Yes, from the beginning Satan tends to shift responsibility to God or duty, but he himself recognizes this as a way of avoiding his own shame (1.641, 4.388).

The trouble with limiting Milton’s Satan to a mockable figure, which C.S. Lewis among many other notable figures have erroneously done, is that it pigeon-holds Milton’s multi-dimensional character of Satan. Milton was not writing a textbook on Genesis, but recreating a dramatic portrayal of what it means to self-sabotage through the characters of both Satan and Adam/Eve.

The belief that Milton did not wish us to sympathize with Satan is only half true: In my opinion, Milton did not want us to sympathize with Satan and stop there; that is only half the process. Milton’s cautious interjections actually support my theory because Milton’s warnings are the voice of reason and justice to harmonize with the voice of compassion and sympathy which he plainly inspires in Satan’s soliloquy’s. Stein brilliantly observes that, “one need not choose between Satan being a tragic hero or an absurd villain. Either extreme stamps us as a more restricted moralist than Milton the poet. For then we are less able than Milton to admit the test of contradiction into the moral universe of our art,” (3). In my view, the tension between the sympathy and rejection one feels for Satan was an intentional device Milton (or his Muse) used for a specific purpose.

2. THE FATHER OF LIES

Milton alluded to Virgil and Homer’s epics repeatedly throughout Paradise Lost, especially in Book 1. Another major epic which Milton was intimately acquainted with is Dante’s Divine Comedy. Some speculate that Milton was actually re-reading Dante's Commedia while he wrote Paradise Lost (Samuel 33, 44-45). Just as Dante’s hell was an allegory for the hell on Earth which humanity creates for themselves through their sin, I argue that Milton’s character of Satan is also an allegory for the hardened nature of fallen and damned human souls. Reading Paradise Lost in light of this, one can delve into the psychology and self-made obstacles of fallen humans and, in effect, our very own fallen selves.

What is curious about Milton’s depiction of the Fall is that he does not write Eve as the first to sin, but makes clear that it was Satan who was the first victim of his own deception (illustrated in Raphael’s account in Book V). This here is the blasphemy of the Holy Spirit: forsaking our conscience and deceiving ourselves, thereby corrupting our own hearts against our Creator. This is what Satan is truly the father of: Self-Deception (John 8:44).

There are two Christian approaches to confronting Satan: the military approach and the approach of the cross. The military approach is when one speaks of crushing the head of the serpent beneath our feet, best illustrated by Michael’s battle against Satan in Book V. The cross approach is when one pities the devil, scrambling in his failed revenge and inevitable defeat. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. famously said, “Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that,” (37). Perhaps when we are taught to love our enemies (Matt. 5:43-48; Luke 6:27-36), one of the most powerful expressions of this is our victorious and all-defeating love and compassion for The Enemy. Pity and compassion for the devil does not condone his actions, but is founded in the knowledge that he is defeated, powerless, and eternally damned in his own self-infliction, alongside every other human soul suffering the same tragic fate. Loving the devil does not arm him with adoration, but disarms him in our undying, sympathetic, Christ-like pity. Could this have been Milton’s hidden purpose in creating such a complex Satan?

I am reminded of the Jewish tradition of yetzer hara: the devil as a metaphor for our own evil inclinations (116, Ben-Chaim). Milton’s own description of the role of our evil inclinations in his Areapagitica supports his understanding of this yetzer hara (whether he did so consciously or unaware of the pre-existing Jewish tradition, scholars differ on the subject) (2:527-8). If Satan is the Adversary, as we live we testify to how the greatest adversary against our own good nature is, in actuality, ourselves. If we can be compassionate towards the devil of Paradise Lost, we can love ourselves at our own worst and root for our own hope of redemption in Christ. What is often our trouble in accepting God’s forgiveness is our inability to forgive ourselves; just as Satan’s own inability to forgive himself, “So farewell hope, and with hope farewell fear,/Farewell remorse : all good to me is lost,” (4.108-9).

Milton has given Satan a soul, a damned soul, but a soul. And for what purpose did Milton direct his energies into accomplishing this? I have found that Milton was actively building upon Augustine’s Deprivation of Goodness. Satan is not the Evil Force in the universe combatting Goodness, but instead, and in a return to the more traditional understanding of yetzer hara, Satan is the embodiment of goodness corrupted, and therefore the true firstborn of fallen humanity.

Just as Milton did not end his epic with the Fall, but with Paradise Regained, so I must follow suit and conclude this essay properly by pointing to the revelation of Jesus Christ as the firstborn of the new humanity; the embodiment of goodness redeemed. This is the fourth part of the story which has yet to be masterfully dramatized in modern epic fashion: the Recreation. I must admit, I avidly await it.

Works Cited

Aristotle. Poetics. Translated by Anthony Kenny. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Ben-Chaim, Moshe. Judaism: Religion of Reason. Mesora of NY Inc, 2011.

Dostoevesky, Fyodor. Notes from the Underground. Mineola, NY, Dover Publications Inc, 2012.

Fish, Stanley Eugene. Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost. Harvard University Press, 1998.

King Jr., Martin Luther. Strength to Love. Pocket Books, 1963.

Lewis, C.S. A Preface to Paradise Lost. New Delhi, Atlantic Publishers & Dist, 2005.

“Paradise Lost”, “Areapagitica”. Luxon, Thomas H., ed. The Milton Reading Room, http:// www.dartmouth.edu/~milton, March, 2015.

Samuel, Irene. Dante and Milton: The Commedia and Paradise Lost. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1966.

Shawcross, John T. With Mortal Voice : The Creation of Paradise Lost. The University Press of Kentucky, 1982.

Stein, Arnold. Answerable Style : Essays on Paradise Lost. University of Minnesota Press, 1953.